PROLOGUE: My last “blog” post about my personal history was about Cortland Ohio. It featured my hometown and my Grandfather, William Alba Harned.

My father was born in Conneaut Lake, Pennsylvania. Both of his grandfathers had farms there and as a young boy I visited western Pennsylvania frequently. For now we will skip the generation of my dad, William E. Harned, who recently celebrated his 90th birthday, to take a look back further into some more general history.

Without boring you with generations of the Harned family tree or names that go back to an Edward Harned, who left Sandwich England for an English colony of Massachusetts, or stringing my connecting generations through New Jersey and other parts of Pennsylvania; I want to share a (rather long) excerpt of context of Pennsylvania history, all from one source. I trust you American history buffs will enjoy some of this.

Link below to full article on Somerset Co. PA, location of Harnedsville PA 15424

HARNED family – Some Pennsylvania History –Excerpt.

We pick up the story of William Penn’s English lands about 250 years ago. I have highlighted first references to each year to help us follow the timeline of American History.

Bouquet had met and defeated the Indians at Bushy Run, August 5, 6, 1763, thereby shattering Pontiac’s dream of redeeming the wilderness for the Red Man.

CHAPTER IX – No Trespassing

From a military point of view the lands west of the Alleghenies to the Ohio were now cleared of both French and Indians, and therefore subject to the seeds of English culture. A civilian, viewing the grounds from another angle, saw a hotbed of cross purposes. There were the hunter, the trader, the land speculator, the pioneer settler who based his land claims upon squatter rights, and the Indians.

In 1767 there had been an extension of the Mason and Dixon line which showed that most of these citizens lived within the bounds of Pennsylvania, and a number in the future Somerset County. Sensing inevitable clashes among these people because of their different interests, John Penn, Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania, attempted to avert trouble by advising the Assembly to pass a law to remove the people now settled in these parts, and to prevent others from settling in this area of the province.

With the exception of the strip of land now known as Allegheny, Northampton, Southampton, Fairhope, Larimer, and Greenville Townships, the remaining sections of Somerset County were included in this forbidden territory. Ostensibly the order was to prevent fresh clashes with the Indians from whom this land was not yet purchased.

Accordingly John Penn appointed the Reverend John Steele of the Presbyterian Church at Carlisle, John Allison, Christopher Lemes, and James Potter to make known and explain the law to the settlers. Leaving on March 2nd, 1768, they traveled by way of Fort Cumberland, and the Braddock Road to the Western settlements.

The following autumn, November 5, 1768, the Penns made another treaty with the Indians, called the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, in which all the forbidden lands were purchased from the Red Men for the sum of ten thousand pounds.

After acquiring the Indian title the Penns immediately offered this land for sale for five pounds sterling per one hundred acres, and one penny an acre per annum quit rent. Just who was the first person to receive the first warrant in what is now Somerset County will probably never be known, but there is one warrant in Elk Lick Township that bears the date of April 12, 1769, or just nine days after the opening of the land office.

CHAPTER X – The Promised Land

Twenty-five years before the Reverend John Steele was commissioned to remove the settlers from this territory, an entry in an old diary discloses a scene along the Juniata River of a young man and his wife who are determined to “go on The Western Ride to the land of the Turkey Track.”– “they crossed over the river with many calls back and forth of sad farewells, and so off into the woods to the west-running waters.”–“Says he wishes to be reborn again, and so they go to the promised land.”

More than ten thousand men, including the armies of Washington, Braddock, Forbes and Bouquet, crossed and re-crossed the promised land of Somerset County before there was recorded officially the name of one permanent settler.

Most of this land was marked, “Indian Territory” on the maps and ledgers of the Penns; therefore anyone living here was, according to the provincial authorities, out of bounds, off the record and disinherited. But to neglect to enter a name on a docket in no wise affected the men and women who were clearing the land, building cabins, and reaping the golden ears from their patches of squaw corn.

But when the time arrived, April 3, 1769 at 10 o’clock A. M., City of Philadelphia, for the sale of land and the collection of quit rents by the Penns, a survey and inventory of their flocks became a matter of prime importance. The disinherited automatically became bona fide citizens; subject to the benevolent governing powers of the Penns, and taxes.

CHAPTER XI – Home to the Mountains

The lure of far away places has always tugged at the heartstrings of people in every land; particularly when their pastures are not so lush. Having heard of the rich mountain valleys that lay among the great folds of the Appalachians, a group of people living along the mosquito infested flats of Essex and Morris counties in New Jersey decided to seek new homes in the virgin wilderness of the Penns’ domain.

In the spring of 1770 a little band of these discontented settlers loaded their worldly goods upon the backs of their oxen, and started toward new homes in the western mountains.

Following the general course of Braddock’s Road to the Negro Mountains, they swung into the narrow vale of White’s Creek and thence north to the Valley of the Laurel Hill Creek. Arriving here about the first of May they pitched their tents, after which the “men folks” went forth to select a portion of land on which to build a home for himself and his family. By mutual understanding among themselves each one was to be limited to such quantity of land as he could walk around in a single day. In all there were about eighteen or twenty families. Tradition gives us the names: Robert Colborn, David King, Oliver Drake, William Rush, Andrew Ream, Reuben Skinner, John Mitchell, John Hyatt, William Tannehill, James Moon, Edward Harned, David Woodmancy, John Copp, John McNair, Joseph Lanning, William Brooke, Jacob Strahn, Obadiah Reed, and William Lanning.

With the Turkeyfoot settlers as their nearest neighbors these families flourished like the green bay tree; establishing permanent landmarks which are now known as the Jersey Settlement, Jersey Church, Draketown, Drake’s Mill and King’s Mill (two of the first grist mills in Somerset County) Harnedsville, forts and block houses which formed the nuclei of the present towns of Ursina and Confluence.

Apple orchards, cleared lands, and military and civil records are fitting monuments for the spirits of these brave pioneers.

Signs and symbols, carved in the rocks by the hands of our ancestors, are uncertain accounts of the lives they led. The most expert archaeologists disagree as to their exact meanings.

Written words bind the past to the present as no other medium can. Unfortunately the early settlers of Somerset County were spare to the point of parsimony in their use of the quill and inkpot.

Harmon Husband, riding horse back into the Glades in 1771 was farther removed from the Atlantic settlements than the sons of Penn were from the powers beyond the sea. In common with the hunters and a few settlers of the Glades, Husband now belonged to that small band of pioneers who had snapped the last tie that bound them to the traditions of the ages-in short he belonged to the disinherited.

Before coming to the Glades Husband had spent his early boyhood days in Chester County, Pennsylvania and Cecil County, Maryland. As a young man he went to the province of North Carolina, where he gained property, position, and influence. In the role of a reformer he was instrumental in marshalling the forces of the common people in that province. He called them the Regulators or Sons of Liberty.

The pivotal issue was taxes.

Tryon, the provincial governor of North Carolina, was well versed in the well known, universal, and timeless game of subtraction and division; that is, taxing his subjects to the utmost to maintain himself and his small group of satellites in royal style. But Tryon made the fatal mistake, as many have before and since, of over-adjusting the thumbscrews of taxation. The result was rebellion, climaxed by the Battle of Alamance-the first battle of the American Revolution which was fought May 16, 1771. At the sound of the first clash of battle, Harmon Husband, the leader of the Sons of Liberty, jumped on his horse and fled.

In fairness to Husband, who was a Quaker, indoctrinated with principles which would not allow him to fight, he had the courage of his convictions, and when forced to display these inner truths, there was no show of hypocrisy.

There is a monument at Hillsboro, North Carolina to twelve of Harmon Husband’s compatriots who were hanged by the neck until they were dead by the British Governor on June 19, 1771, or about the same time that Husband was being reborn and rechristened in the cool shade of a Somerset County maple grove.

CHAPTER XV – Revolution

South of the line that forms the lower boundaries of Addison, Elklick, Greenville, and Southampton townships it is conceded that the Battle of Alamance was the first battle of the American Revolution with Harmon Husband as the leader of organized resistance to the British Crown. North of the Mason and Dixon line the poet tells us that it was at Concord where the “shot heard round the world” was first fired on the 19th of April, 1775.

Both have ample proof for their opinions, while all agree that frontier Americans held high the torch of Liberty, and with their squirrel rifles, defended that light to their death.

The pioneers of Somerset County (called Bedford County at the time) were no exceptions. Under the command of Captain Richard Brown, with James Francis Moore as first lieutenant, men from the region of the Turkeyfoot, Cox’s Creek Glades, Stony Creek Glades, and along the Forbes Road shouldered their flintlocks and joined Washington’s forces. Few returned.

The account they gave of themselves is a saga in itself.

On the home front there was far more excitement than in the year of 1763 when Pontiac let loose his savage wrath. The simple reason for this was that there were many more settlers here during Revolutionary days, and the battle lines were drawn on both sides of the mountains. The ablest fighters had emptied the buck horn racks of the best rifles, and had marched eastward to meet the Red Coats, leaving the older men and boys with worn and rattling flintlocks to guard their cabins and families against Indian raids from the west.

With the British holding the western military forts it was their strategy to arm the Indians with long rifles, scalping knives, and fire water, and send them to the frontier settlements with murderous intent. The Indians, aided by a few renegade whites, such as the Girtys, cut a staggering red swath through the mountain clearings.

Express riders, the spearhead of civilian defense, galloping from the Forbes Road to the Cox’s Creek Glades and Brothers Valley shouted to the panic stricken settlers:

“James Wells from Jenner Fort shot by the Indians! Flee for your lives !” (Autumn of 1776)

“The Indians have attacked Fort Stony Creek! One of our men killed !” (November 27, 1777)

“Five people killed by the Indians over against the mountains!” (Shade Township, November, 1777)

Harmon Husband removed his family to Fort Cumberland, himself returning to his farms near the close of the war to find (March 1783) that the Somerset settlement had not been invaded. By the spring of 1784 nearly all the settlers had returned.

CHAPTER XVI

Rum and Rebellion

The final draft of a peace treaty between England and America was signed on September 3, 1783, leaving the swaggering young Republic to face the cynicism of the adult nations of the world.

Growing pains of the infant empire were mistaken by the Old World for more serious maladies.

The Big Three who held the bottle of Soothing Syrup for the wriggling young America were George Washington as President, Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasurer, and Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State.

Hamilton believed in a strong central power that would command the dignity and respect of the “common herd.” Jefferson had ideas of his own. Faced with a $77,000,000 war debt, Hamilton conceived the idea of placing a small tax on all spiritous liquors.

At the time there were, according to estimates, 5000 distilleries in Pennsylvania with at least 24 within the present bounds of Somerset County.

Now the idea of government officers entering private homes, measuring the products of the stills and collecting taxes for the same was not, according to the principles of the mountain settlers, among the ideals they had fought for. There was also the spectre of a swarm of these “revenuers” with their hands in the public coffers.

The reactions of the mountain folk to these measures were mass meetings of protest, and some rather rough handling of Hamilton’s agents.

CHAPTER XVII – Peace Comes to the Frontier

The Old West was gone. The frontier that had been the Stony Creek Glades was pushed back to the Ohio and the Mississippi. The log cabin, the long rifle, the axe and the plow took the place of the bark huts and the stone hatchets of the Shawnees and the Mingos. Jehovah watched over the smoking chimneys of the clearings in the forests of the Alleghenies and the Laurel Hills, while Manitou shrieked in vain protest when the winter winds whistled between the black teeth of the spiked stockades.

The settler’s keen axe was biting deeper and deeper into the bush. Log cabins mushroomed overnight, clustering together, and taking names like Berlin, Somerset, Meyersdale, and Stoystown.

Whether the war-whoop sounded or not, the result was the same. Fearing to return to their clearings, many of their crops rotted on the vine, promising lean fare for the coming winter.

Sickness and death have always dogged the footsteps of even the most hardy pioneers. Because no disciple of Hippocrates had come, or remained in the wilderness of Somerset County to aid and comfort the afflicted, each family resorted to healing powers at hand. Every cabin had its herb garden, or lacking that they stripped the bark from the wild cherry, the slippery elm and the sassafras to brew health restoring potions.

In the days before the little red school house in Somerset County children were brought up in the way that they should go, without specialists to guide or perplex them in the rough hewn paths of learning. Boys were taught early the use of the Dutch scythe, the broad axe, and the flintlock. In the matter of letters few mastered the fine art of the three R’s.

Those who did were introduced to them by the way of well thumbed Bibles.

Girls were taught the tunes of the rhythmic whir of the spinning wheels and the intricate steps of the hand loom. One of the first attempts to bring regimented “book larnin’” into settlements of Somerset County was in the year of 1777. James Kennedy, one of Harmon Husband’s indentured servants, who was a poor hand at grubbing and picking brush, was chosen to lead, guide and direct the lives of the little children of the Somerset Settlement. The young schoolmaster, after surveying and questioning his home spun class for a few minutes dismissed school with the admonition, “Och! but you are set of young haythens.”

Law and order were maintained in the clearings by adhering to the simple and age old verities that have served as cornerstones for civilized societies in all times. Without sheriff or justice, the thief and the liar were humiliated by public condemnation until the culprit sought peace of mind and body in some distant settlement where his sins could not find him. In the matter of more personal offenses against honor and virtue, the score was usually settled by other members of the families involved, in rough and tumble fights which in many cases developed into ear chewing and eye gouging matches.

The vitriol of female wagging tongues was neutralized by the simple and effective device agreed upon by the more rigid pillars of the settlements. When the gossips appeared in their doorways, they listened with the usual absorbing feminine inquisitiveness while the mush bubbled in the pot, but discounted every dripping word as child’s chatter. In short the gossip was granted a license to talk, and even the “news” of an impending Indian raid caused not one stitch to be dropped by the knowing housewives. The spinning wheel, hand loom, and the backs of ‘coon and deer were sources of material for dress. The hunter’s frock, a knee-length fringed coat made of home spun cloth or buck skin was universally worn by the men. This garment was fitted with a belt upon which hung the tomahawk and scalping knife. Lapping over in the front it could be used for a pouch in which to carry provisions in the form of dried venison, salt pork and bread. Coon skin caps, buck skin shirts, and leather stockings were further protection against sleet and snow.

Moccasins served as footgear. These were made of a single piece of deer skin with a gathering seam along the top of the foot, and another from the bottom of the heel, and tied about the ankle with thongs of deer skin. In cold weather they were stuffed with deer hair or dry leaves. During rainy weather and slushy seasons this gear was looked upon as “a decent way of going barefooted.”

Among the various religious setttlements of the county their several faiths dictated their mode of dress.

Moving on to this day, while touching area history about 100 years later:

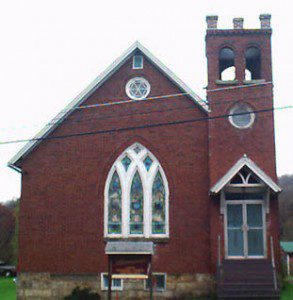

The Harnedsville Church is located in the village of Harnedsville, just south of Confluence, Pa, in Somerset County. The mailing address is: 1643 Listonburg Rd, Confluence, Pa 15424.

Harnedsville Evangelical Congregation started about 1870, in a log school house at Walker’s Mill. The first preacher was Rev. George White, a circuit rider from Preston Co., WV.

In 1910, a new church was built in the village of Harnedsville on land acquired from Thomas and Elizabeth Bird. It was dedicated as the “Memorial United Evangelical Church”. It is the church in which we still worship. In 1946, the Evangelical Church merged with the Church of United Brethren in Christ to form The Evangelical United Brethren Church. In 1968, the Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren Church united, and became the United Methodist Church, of which we are members today.

Sunday morning worship is 9AM, followed by Sunday

School at 10AM.

Directions: From Somerset, take Rt. 281 south to

Confluence, Pa. Turn left on Rt. 523 and drive 2 miles.

Church is on right.

Pennsylvania is an interesting state with even more interesting history. Before you visit Harnedsville, consider a visit to Gettysburg or the old home of American government in Philadelphia to learn much more.

P.S IF you were following the Revolutionary War timeline and would like just another bit of PA history, about this time of year in 1777 our new government was running for their lives.

Things began looking grim for Philadelphia, the old capital city, in September 1777.

British forces under General William Howe had been advancing north from the Chesapeake Bay in an effort to capture the revolutionary capital, and American forces led by George Washington had moved south of Philadelphia to intercept the invading force. On September 11, Washington’s men clashed with Howe’s troops in the Battle of Brandywine.

The battle was a catastrophe for the Continental Army. Howe outmaneuvered Washington, and the rebellious colonists had little choice but to retreat

On September 26, 1777, the British waltzed unopposed into the City of Brotherly Love.

The delegates packed up their gear and hoofed it 60 miles west of Philly to Lancaster. On September 27, 1777, just one day after the British strolled into Philadelphia, the Continental Congress met in Lancaster’s county courthouse, a building that had been constructed in the town square in 1737.

Just like that, Lancaster became the third capital of the fledgling nation. (Baltimore had also briefly served as the capital between December 20, 1776 and February 27, 1777.) The Continental Congress got some work done that day, including electing Benjamin Franklin as commissioner to negotiate a treaty with France, but the delegates didn’t have much time to get comfortable.

ON THE ROAD AGAIN

Even a 60-mile buffer from the British forces in Philadelphia seemed a bit thin given the easy march the red coats had just made into the old capital, so after one day in Lancaster, the Continental Congress again packed its bags. This time the delegates headed to York, Penn., which offered another 20 miles of cushion from the British. Plus, York was nestled on the western side of the Susquehanna River, which made it easier to defend from potential British encroachment.

The Second Continental Congress had a longer stay in York. The delegates met in York’s courthouse from September 30, 1777, all the way through June 27, 1778, at which time the congress moved back to Philadelphia.

Lancaster wasn’t the only unexpected capital in the country’s early days—Princeton, Annapolis, and Trenton all had stints of their own under the Articles of Confederation—but its time at the top was certainly the shortest. Today we tip our caps towards Pennsylvania in honor of the 236th anniversary of Lancaster’s brief moment in the sun. Read the full text here:

Leave a Reply